Last winter I gave a speech called “How Baseball Made Me into a Feminist.” The title attracted more curious people than the room could hold: after all, how could baseball turn anyone into a feminist?

In two ways. First, marrying the man who would become the first scholar ever to write baseball history plunged me into baseball research. He needed my help because of my skills in writing, editing, and research. Since I was born in 1928, I grew up at a time when women were taught that wives helped their husbands without the expectation of proper credit and when men assumed that they deserved their wives’ help. So I permitted him to receive all the credit for the preparation of books for which I deserved equal recognition.

It took me a while to realize that I was in the same position as thousands of other women who permitted themselves to be exploited by their husbands or other men. After my husband’s passing in 1990, I began revealing my real role in the publication of the first scholarly history of baseball. Not until 20 years later did Oxford University Press decide to republish those books with my name added to the title pages. The whole experience of understanding that I had been exploited by my husband over our 40-year marriage rooted me firmly in the feminist movement.

The second way that baseball made me a feminist was my discovery, through research, that women who loved to play the National Game, had been playing it since the 1860s, and that some had developed into very good players, but they had been constantly ridiculed, denigrated, and rejected by the baseball establishment. Even those few who were actually signed to minor league baseball contracts had undergone the experience of having those contracts cancelled by the baseball commissioner simply because they were women. (In those days, discriminating against a person because of her gender was perfectly legal.) With that kind of history, female baseball players stopped trying to become a part of the dominant baseball organization. Consistent rejection has that effect. When I realized that these women’s experiences were akin to mine, my position as a feminist was reinforced.

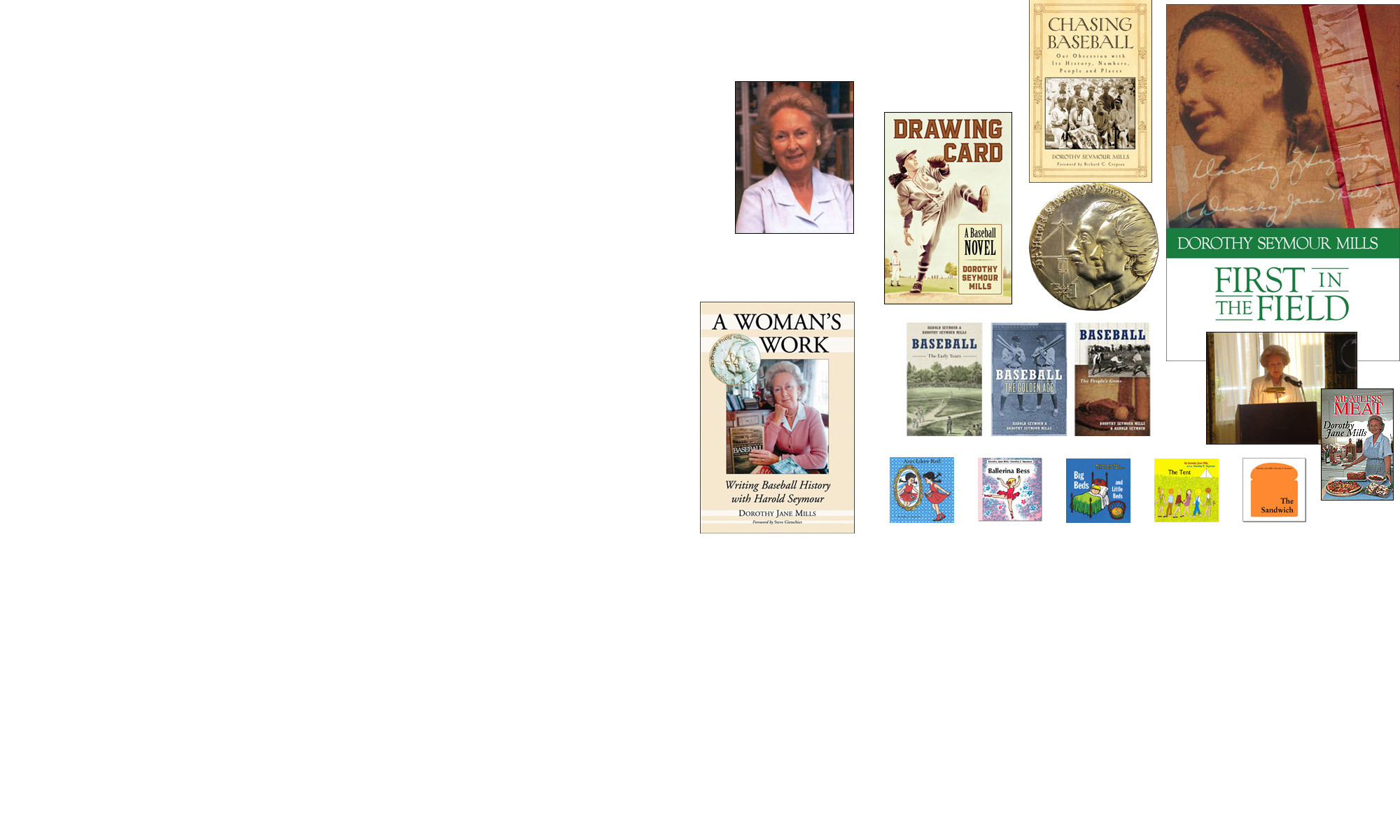

My writing career has sprung largely from these life experiences. Although some of my 26 books are unrelated to baseball, most of those that are still in print relate in some way to the National Game. My autobiography, A Woman’s Work: Writing Baseball History with Harold Seymour (McFarland 2004), surprised and dismayed many who believed that Harold Seymour had somehow managed to perform independently all the research, organization, and writing entailed in producing the monumental three-volume series on baseball history for Oxford University Press. Proving otherwise was most gratifying. A review of this book on amazon.com reads:

When Mills determined to tell the truth of her unacknowledged collaboration with her much-lauded husband, baseball historian Harold Seymour, she did it in her own style: with meticulous documentation and lucid prose….While there’s a notable lack of anger in her tone, neither is there a glossing over or romanticizing of the way things were for a woman aspiring to write back in the late 1940s.

This year I underscored the main point of my autobiography by producing a related publication. For an electronic book publisher I wrote an eBook single, First in the Field: My Journey as the First Woman Baseball Historian. A review of this book on amazon.com reads:

There is more to this book than meets the eye. This book captured my interest because of the author’s story about her struggle to be recognized for her research and contributions to the history of baseball. This is actually a book for a Women’s Studies class. It describes the times that women in the postwar period lived through. It tells a story about one woman and how she became liberated. The author, through her determination, freed herself from a subordinate role of the traditional woman while many other women of her generation never reached that point. It is difficult for women to describe this role which is still hiding under the surface in many marriages of couples of a certain age. Dorothy Mills does it well. That the book is based on the history of baseball adds an interesting feature.

My most recent book, a historical novel called Drawing Card (McFarland 2012), was inspired by those baseball-playing women whose minor league contracts were nullified by the baseball commissioner simply because of the players’ gender. Each of these players responded to their rejection in the way women were supposed to react: they went home quietly and found some other athletic activity to engage in. I wondered what would have happened if one of them, instead of withdrawing politely, became so deeply angry that she couldn’t stop thinking of how to strike back at that commissioner. So I sat down and tried to imagine what might happen.

Writing Drawing Card as a historical novel enabled me to include flashbacks to events in women’s athletic history showing how they have long been prevented from realizing their full potential in this field. One of the reviews of Drawing Card on amazon.com reads:

A great work of historical fiction, Drawing Card takes the reader into a world many are not familiar with while others are all too familiar. The story, through fictional, is based on the many stories of women who wanted to play baseball at various times in history but have been denied that chance. It is a timely story as this is still an issue faced by young ladies today. Drawing Card will get people talking about baseball and

equality of opportunity.

My next book is directed at young people. Not long ago I began to realize that if attitudes toward women’s baseball are to change, we must start with the young, who still believe that only men play the National Game and that only men have developed baseball stars that youth can try to emulate. Young people have no idea that history contains women baseball stars. They have heard of Babe Ruth but not Babe Didrikson; they have some notion of Jackie Robinson but have never heard of Jackie Mitchell.

This book is a history of women’s baseball for young people. It will be published in the form of an eBook, since that is the form in which youth prefers to read. I hope that the ideas in this book burst upon them like a pricked balloon. Surprise! Women play baseball. Surprise! Some of them play it very well. And more surprise! Some of the players of the past should have, and could easily have, played in the minor leagues. Some almost did. And you shouldn’t be surprised when one day they do.

Recently, feminist blogger Gloria Feldt has recognized my work in her blogs. In “Settling the Score: Dorothy Seymour Mills Finally Tells Her Story” and “She’s Doing It: Dorothy Seymour Mills Finds Her Voice–and Uses It!” Feldt shows her readers the importance of my two latest books.

If you would like to consider using any of my books with your students, I will be glad to send copies. Thanks for taking the time to read this.

— Dorothy Jane Mills