I’ve noticed something about myself: I’ve developed a lot of pride in my work. When I’m with others who are speaking of their activities, it’s often with seniors like me. Most of them have retired from work, and I like hearing what they have done in their work lives. During the conversation I often find the opportunity to report that, despite being 78 years old, “I’m still working.” I’m proud and happy that even at this age I’m able to continue actively with my lifelong devotion to the work I love.

Work is of value to me. It’s a pleasure, a delight, a big part of my life. I don’t ever want to quit working.

Not everyone my age feels this way. Some can’t wait to retire. Some can’t afford to. I recall my brother saying to me back in the 1960s, “Do you know what? Dad hates his work. He’s still working at this advanced age only to earn a better pension, so he’ll feel more comfortable when he retires.” Sadness engulfed me, remembering Dad’s former pride in his work as a printer when, as a child, I watched him at his press. He produced beautiful printing because he insisted that his press and his co-workers perform to high standards. Since then he’d evidently burned out.

Once I burned out, too. I was a teacher for seventeen years before quitting because I could no longer function to the high standards I had set for myself. I knew it was time to leave and focus instead on my greatest pleasure, working with words. So I did, and I’ve never regretted the decision. By then I had already become an author and editor, so the transition was easy, and I was soon working at what I believed to be the top of my form as a full-time editor, writing on the side. I was proud of what I could do.

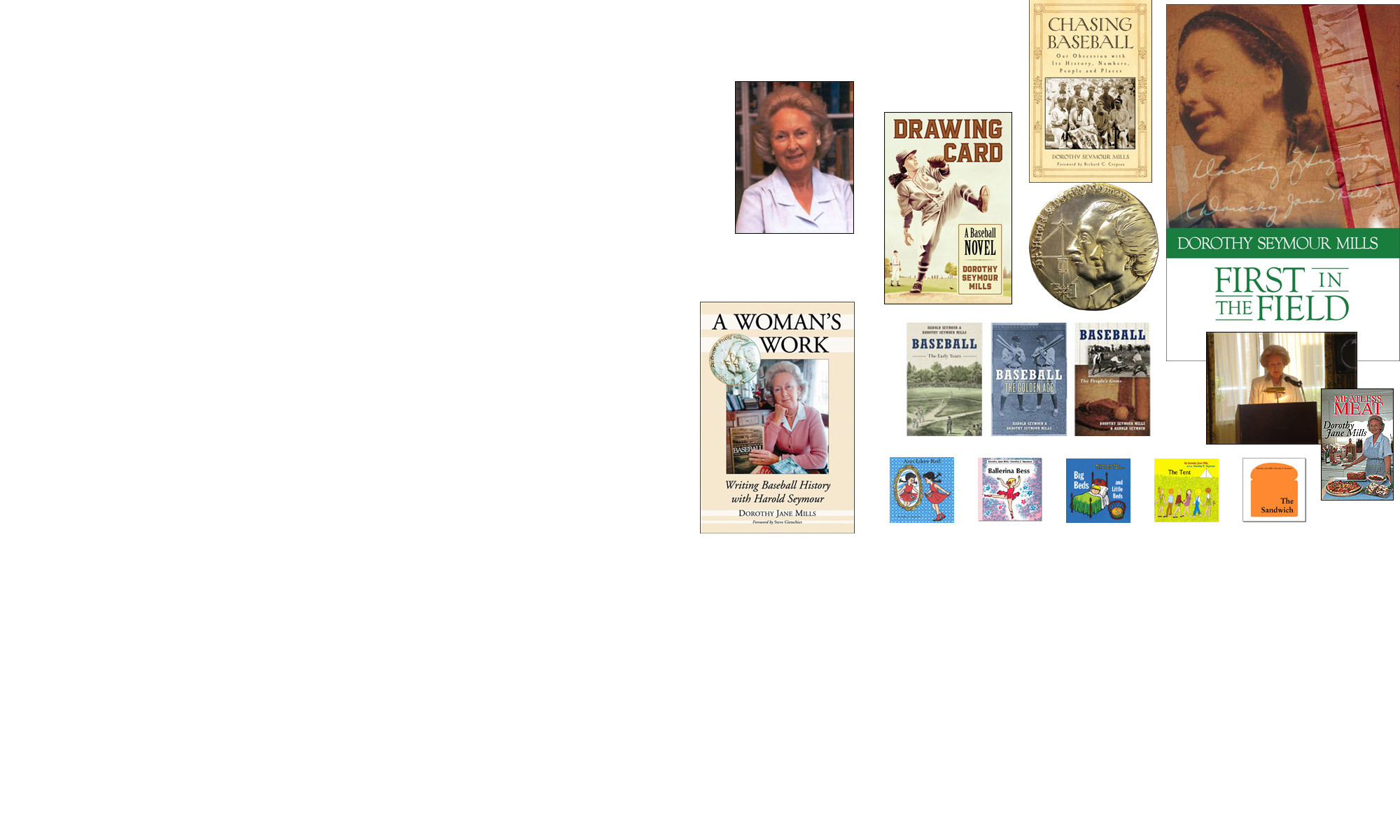

But since leaving full-time editing I have performed at an even higher level, producing creative work (in the form of books) more complicated, original, and imaginative than I had realized I could conceive. Nothing I’ve ever written has been more satisfying than my work of the last ten years.

So I’m convinced that creativity and productivity can actually increase, not decrease, with age. To a certain point, at least. I know I’m slowing down, but that makes me concentrate and focus my efforts more. I get up earlier in the morning. I can hardly wait to get to my desk. And I’m proud of the work I produce.

Work is one of the most important parts of our lives. It contributes to who we are–it shapes us as persons. The kind of work we do matters little, as long as we find it satisfying.

One can really be happy performing work that’s not necessarily prestigious. I remember the father of a pair of twins I was teaching in Pelham, New York. When I took the class to the playground at recess we often saw their father at his work. He was a garbage collector, and he obviously took pride in doing a good job, giving us all a cheery wave and a smile. In the community where I live now, that same cheery wave and smile are bestowed today by the man who operates the grass mower in my community. He zips around handily in his machine. He’s never “down,” always seemingly happy. The same with the woman who delivers the mail: she is always volunteering to do extra things for her customers, and she’s perpetually friendly and pleasant.

Such jobs can be creative, too. They need not be prestigious occupations to be satisfying and creative. I believe the Germans realize this. I can tell by their wording of a common query. Here in the U.S.A., when we notice a friend or family member engaged in some sort of project in the garden or kitchen, or at the computer or sewing machine or craft bench, we ask, “What are you doing?” Not the Germans. In their language, they ask instead, “What are you making?” (Was machen Sie?) That wording implies the creation of something new, even if it’s intangible. I think the Germans have something there. The American Heritage dictionary points out that “work” can mean either physical or mental effort, but it’s always directed toward either the production of something or the accomplishment of something. Producing or accomplishing something is a creative activity, one in which we can take pride.

Occupations we think of as non-prestigious can be the most satisfying. I never realized this until, not long ago, during a period of one week I heard two women assert that the time they spent waiting on tables was the time that was the most valuable to them, the time when they learned the most. Intriguing. The first woman had enjoyed careers as a teacher and as an administrator, but she thinks fondly of her waitressing years. The second woman is a dental hygienist and an accomplished technician, but she adores her “Sunday job” as a waitress at a popular local restaurant because its regular customers have become her “family.”

To some, research falls into the category of non-prestigious work. Not long ago a woman posted an e-mail message to a listserv I belong to, calling research “grunt work.” That description of it implied that research was tedious and boring. I took issue with her claim, asserting that I found research comparable to a treasure hunt: as soon as I locate one fascinating fact, it leads me to think of a place where I might find some related information, and when I get there I am led somewhere else. This phenomenon continues and extends itself, and I become more and more excited, until soon I’ve uncovered a whole network of information, connected like a web, that falls together into a story. Little except completing the writing itself compares with the thrill of that hunt and its multiplying discoveries.

So the value of an occupation remains a matter of opinion. That leads me to think of the “woman’s work” and “men’s work” controversy. Even the controversy rests on the assumption that we all have some work to do in this life. And now that the line between male and female occupations has blurred so much, we can all probably agree that, even when we’re taking a holiday, we return afterwards to perform “our regular work,” whatever it is, at home or at the office or shop or fields, or on the sea or in the air.

Those of us who work tend to think less of those who don’t. I believe “playboys,” those who seem to do nothing with their lives but play, carry less envy and respect than they used to. We seem to realize nowadays that there’s a lot of work to be done in this world, and we’d like everyone to carry his or her share of the burden. For some, the burden of their work is light. For others, it’s heavy. Yes, some work is dull, wearisome, and monotonous. For me, ironing and sewing are dull and monotonous, but I still perform them when I think it’s necessary. And I know I can always return to the joyous kind of work I do, the kind that gives me great pleasure: working with words.

There’s an ancillary benefit to working that has been brought home to me in recent years: we make friends through our work. Some of my longest-lasting friendships are with people I met through jobs I’ve held. Besides being warm and friendly, these people have interests similar to mine, similar views of life, and similar experiences. Those are the initial characteristics that made us grow close. And now we have memories in common, too. Memories of working together.

I’m glad that I experienced a life full of interesting work. And I’m even gladder that I’m still working.

— Dorothy Jane Mills