This column was first edited by Ethan Casey of Blue Ear, and was edited again by Geof F. Morris of TOTK.com Sports. This column was first co-published at Blue Ear and Sports Jones. All rights are owned by Dorothy Jane Mills.

By Dorothy Jane Mills

At once glorious and ignominious: that characterizes my work with Dr. Harold Seymour, “The Gibbon of Baseball,” the man who made the American national game a respectable subject for formal study by historians, the author of the first scholarly history of baseball.

Glorious because I learned how to perform (and love) research; ignominious because my contribution to the work remained unrecognized until after his passing in 1992, although I spent forty-six years working closely with him, first on his dissertation and then on his three-volume series for Oxford University Press, now the standard books on the subject.

Dr. Harold Seymour, a professor of history as well as a lover of the game, has a welldeserved reputation as an innovator. He boldly opened the field of baseball as a subject for serious study. Before him, no other historian had dared to suggest that the word “baseball” might be uttered in the same phrase as the word “history”. Only sportswriters had ever tried their hand at writing baseball history, and the journalistic accounts they produced were so flawed that they earned no standing in the eyes of professionals.

Only one other scholar had previously ventured into the realm of sports history: John R. Betts, who produced a book that attempted to cover the history of all of sport. Before Seymour, no historian had tried to approach the American national game as a subject for serious study.

Seymour got the idea for a study of baseball in the early 1940s while casting about for a topic for his Ph.D. dissertation at Cornell University. When he wrote the paper for his master’s degree, he felt it necessary to choose a topic from his lead professor’s field, which was land policy, but he found it deadly dull. He decided that the only topic that interested him deeply enough to write about it on the doctoral level was baseball.

Harold had always loved the game. As a child growing up near Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, he racked his brains to think of ways to get in and see his heroes. He thrilled when he was selected to help pick up trash in the park or work on the scoreboard, and he exulted when he was chosen to be batboy. Moreover, he played the game and coached other young men when he was in high school and even at college. Although he realized his skills weren’t quite good enough for the professional level, he was able to help other young men become pros.

When he began undergraduate work at Drew University in New Jersey in the thirties, he thought he might become a physician, but the long afternoon laboratory courses in science interfered with his baseball play for the college, so he changed his major to history and decided to become a teacher, assuming that he would coach baseball on the side. Unexpectedly finding great pleasure in the study of history, he went on to Cornell for his master’s degree and realized that, to teach at the college level, he needed a doctorate.

One warm and sleepy afternoon at Cornell, during a class in which Seymour was to present and describe the topic he had chosen for his doctoral dissertation, nodding heads suddenly jerked up as he announced his topic as the history of American baseball to 1890 and explained how and where he planned to perform the research.

Although eyebrows lifted among the committee of professors whose responsibility it was to direct doctoral work, Seymour managed to convince the group that he had a viable and suitable topic.

Fortunately, at that time he had the New York Public Library at his fingertips and spent long hours here on the wonderful collections of early documents that the library still houses — although recently the administration has been thinking of selling them off to collectors. That sale might put them off-limits to current scholars. I may have convinced the library’s administration otherwise, for unless the library decides to keep these documents or the Hall of Fame Library at Cooperstown bids for and purchases them, they may be closed to research.

I met Harold Seymour in 1946, when I was a co-op student at Cleveland State University, then called Fenn College. I grew up in Cleveland and had just been graduated from Collinwood High School. Assigned to Seymour’s survey courses in American history and later in European history, I found his classes stimulating, and when he learned that I was an English major he asked me to do some secretarial work. He discovered that my writing and editorial skills would help him a lot, not only in his course preparation but also in the work he was doing on his Ph.D. dissertation for Cornell University. He had completed the course and residence requirements but was still working on the dissertation.

I was startled to learn that the subject of his thesis was baseball. Baseball has a history? Well, after all, everything has a history, I realized. I was intrigued to find that Seymour had convinced his Ph.D. committee at Cornell that the study of baseball history was worthy of scholarly effort.

It wasn’t long before Seymour and I were friends, and more than friends. He was in the throes of a divorce, and after my third year at Fenn the divorce became final; we were married immediately. But we realized that my being both a student and a faculty wife might prove awkward, so I transferred to Western Reserve and completed my undergraduate degree there, continuing for my master’s while I began teaching. I had planned to enter journalism, but Seymour convinced me to go into teaching instead so that we would have summers together.

When I met Seymour and began helping him with his work, I was still a teenager with little experience of the scholarly world. I failed to realize that the amount of assistance I was giving him in research and organization of materials for his doctorate was probably inappropriate. This was, after all, supposed to be independent work. But because Seymour knew the committee still needed to be impressed with baseball’s potential as a subject for scholarly study, he felt he had to produce an extraordinary product, and he solicited and received my help with research, organization, and writing. I even took a term off from teaching in order to devote full time to research in the Cleveland Public Library, which discovered that not only did it house valuable early guides, magazines, and newspapers, it had accessioned some valuable legal documents hidden on a mezzanine in some big cartons and forgotten for years. The librarians came to know me so well that soon they invited me to have lunch in the staff library.

Material discovered at the Cleveland Public Library, combined with the foundation of documents, newspapers, articles, and books researched in the New York Public, made a convincing basis for a thesis demonstrating how the history of American baseball recapitulated that of other American institutions. The result was a prodigiously long (two-volume) dissertation, one simply full of convincing research evidence.

When Seymour received his doctorate in history at Cornell for a dissertation called “The Rise of Baseball to 1890,” the awarding of that degree received nationwide attention by the news services. Nobody had ever been awarded a doctorate for a dissertation on such a topic as baseball history, and he basked in the publicity.

We began casting around for a publisher, and Prentice-Hall was interested, but decided that, for such a book, the story would have to be brought up to the present. Seymour knew that a scholarly treatment of all of baseball history would be virtually impossible in any reasonable time period, so he looked further. Oxford University Press liked the idea of the book, asking only that the story be extended to a better breaking-off point, which appeared to be 1903, with the establishment of the National Commission.

We began work together not only on the extension of the coverage but also on recasting the work for publication, for the dissertation presented the material in the usual stuffy and formal scholarly style, bristling with numbers referring to footnotes, which had to appear on the foot of the page. In those days before word processing, I often retyped a page a dozen times. Seymour didn’t know how to type.

When Oxford finally awarded the contract, we were living in New Rochelle, New York, and Seymour was teaching at Finch College. We moved into Manhattan and spent as much time as possible at the New York Public Library, which I still refer to as my second home. Summers were spent at a cottage near Monroe, New York, where we completed the manuscript for the book, including the footnotes. However, Oxford decided the book would be too long with notes, so we had to content ourselves with a long bibliographical note instead. Baseball: The Early Years was published in 1960, and Oxford signed Seymour to a contract for what we thought might be the final volume.

In these years I discovered that Seymour did not really like research, while I found it fascinating. To me it’s like a treasure hunt: as soon as I find something interesting relating to whatever I’m researching, it leads me on to something else. Eventually, I learn about a whole chain of interrelated facts or events, ones that haven’t before come to light, and I extend my knowledge of the subject greatly. I find that really exciting.

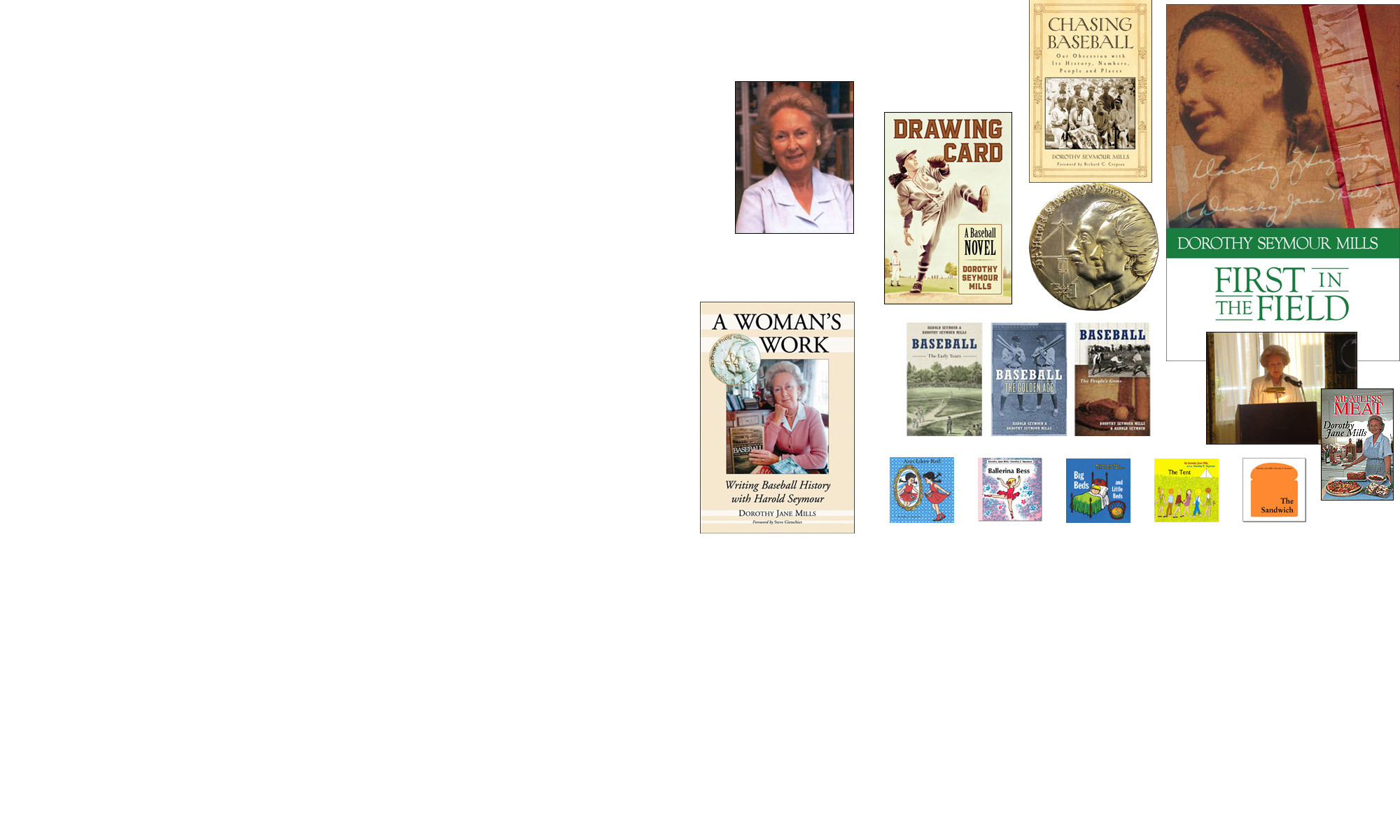

While we were working on the second book, we moved to New England so that Seymour could accept a position as head of the history department for a newly-established community college. I left teaching, for I was really burned out, and entered the field that I should have been in all along: the publishing field. For I had already become an author, producing a series of children’s books for use in the classroom, which were then reprinted for the general trade by Golden Press, and I had written a number of education articles for teachers. I’d also produced a comic strip series for new readers, which appeared first in the local newspaper where we were living at the time (Warwick, New York) and was later reprinted in a children’s magazine.

In New England I first took a year to continue my study toward a doctorate at Boston University, which I had begun at the University of Buffalo, but broke it off to become a senior editor at an educational publishing house in Boston. I also published several articles, some on education and some on other topics. One of them, now more than 20 years old, still brings in permissions fees for republication in textbooks. Evenings and weekends and vacations I continued work on baseball research. I found that the Boston Public Library has some excellent material, as does the Widener Library at Harvard.

Libraries aren’t the only sources for baseball research, of course. I started a wide correspondence in his name. One of his former students, Laura Haywood, helped with this. Together Seymour and I visited historical societies, conducted interviews, and took notes in busy newspaper offices. During this era The Sporting News refused to sell microfilm of its issues, so to read any of the early issues of the paper, we simply had to travel to St. Louis and use those rattly, old-fashioned Recordak machines that the New York Public Library also owned. Once, I took a few days off and flew to Cincinnati alone to take notes on an early newspaper we’d heard would be helpful. Libraries could not always afford to put these sources on film, and often I came home with my clothes full of little yellow flecks from old newspapers that had disintegrated when I tried to turn the page.

We made many trips over the years to Cooperstown, where the library gradually changed from a tiny space to a separate building. At first the library consisted of one small room above the museum, a room that also served as an office for the library’s director. The first director we met was Sid Keener, an ex-newspaperman who, like some historical society librarians, was reluctant to open the material to scholars. Sid was almost as suspicious as clubowners.

Then Lee Allen took over. Lee was genial and friendly. He let us use the Hermann Papers but was curious about what we were finding, so we shared a few discoveries with him. We also noticed Lee’s style of writing his own books: he often decided first what he wanted to say, then looked around in the material for something that might back him up. The scholarly method is, of course, just the opposite: do the research first and see what points it leads you to make. That’s not to say Lee’s books have no value. They have, but they also have severe limitations.

I always put Seymour’s work ahead of mine. For a long time I believed that his work was more important than mine and deserved my best attention. Although I published books of my own-minor education studies, children’s books, workbooks and guides for teachers-along with many articles, my star has always been outshone by Seymour’s, and I permitted this to happen. I even believed, and told him, that “your work is more important than mine.” That was like saying, “You are more important than I am.”

In the seventies I finally convinced Seymour to leave teaching and write full-time, for he wasn’t getting the second volume written and was becoming increasingly frustrated with teaching. Volume 2, Baseball: The Golden Age, was finally published in 1971, and we planned a third volume that would bring the story of the professionals at least into the fifties or sixties.

We thought retiring to Ireland might facilitate the work by creating an environment conducive to writing, but after a couple of years in an Irish cottage, we found we missed our roots in the States and learned that checking our sources was too difficult at a distance. Besides, the Sunday New York Times was delivered to us a month late, and in a rather soggy condition. We moved back to the States, first to the American South, to get the warmth of Alabama, but we didn’t fit in very well there and moved to South Carolina, which we liked.

While we were living in Asheville, my former publishing company in Boston asked me to return to help with a large editorial project. I’d been freelancing with both writing and editing for that company and others, and since the company offered to pay all moving expenses, we decided to make the move North again. The Boston Public Library was again available to us. After a couple of years the publishing company fired all of us who had been hired for the project, and I returned to freelance work. Then we decided to leave Boston, which is pretty expensive for people not holding full-time jobs, and we bought a house in a small New Hampshire college town, where I was shortly asked to work for a small publisher part-time. While living there I published two books on education and several more articles and stories. In Keene, New Hampshire, I also got the idea for the novel I’ve just published.

In working on what was to be the third baseball volume, bringing the story of Organized Baseball into the fifties or sixties, we found we had been collecting so much wonderful new material on the amateur game and semipros that it deserved separate treatment. We convinced Oxford that we should postpone the writing of the next volume on the professionals, set that material aside, and devote a separate book to what became Baseball: The People’s Game. Publication of this book as the third in the series surprised Seymour’s fans, who’d been expecting the continuation of the professional story. The People’s Game was a very fat book, but we still had to leave out a lot of rich material, especially on foreign baseball.

This is my favorite book of the three, mainly because the material is much more homey and down-to-earth than what appeared in the books about the story of the pros. The People’s Game shows how average Americans in almost every walk of life enjoyed baseball in the most loosely organized teams and leagues, playing it largely for pleasure on a social basis, whether they were at work, in the military, in school or college, even in prison. And it brought to light new material on early play by nineteenth-century women, especially in the elite colleges. I loved my bus trips to those New England colleges to examine old yearbooks and college newspapers and discover events in the colleges’ past that staff members were unaware of. I found the material I prepared for this book very appealing. I wrote careful outlines, organizing the notes (with citations for each point in parens), and he wrote directly from my outlines, often using the very words I had chosen.

During this period of the seventies and eighties, I noticed a distinct decline in Seymour’s mental and physical abilities. His bouts of depression lengthened, and his personality traits of irritability and suspiciousness increased. On our last trip to New York together to see his publisher, he refused to let me attend the editorial meeting at Oxford, for he realized that his editor might suspect that I was doing more work on the books than I was getting credit for.

In the late eighties and early nineties, his health worsened, and soon I was not only performing all the research and organization of the material, I was also doing the writing. At first we simply exchanged roles; I wrote and he edited. Then I was doing it all.

When he was invited to Cooperstown to speak, we collaborated on his speech, and I delivered it for him, as I did for another speech we prepared jointly for a SABR meeting at Cleveland State University.

At this time my resentfulness against Seymour’s excluding my name from the title page of his books began to build. I learned gradually that what I was doing was not unusual: wives of writers often worked silently and anonymously behind the scenes on their husbands’ books, getting no credit at all. Jennie Carlyle did this for Thomas, the Scottish historian. Lafcadio Hearn sent his wife Setsuko out to find stories for him; he wrote what she found. Erich Maria Remarque’s wife finished All Quiet on the Western Front for him. I finished Baseball: The People’s Game for Seymour.

Before the book was complete, I presented to Seymour a formal claim for my rights. The acknowledgement pages of previous books had always mentioned my contribution, but I knew that was insufficient. I wanted my name on the title page of the third volume, along with his. On June 1, 1989, I typed a document explaining what I had contributed and asking for the appropriate acknowledgment of my work on the title page of the third book. This is that document in its entirety:

“My name should be included on the title page of this book, for proper recognition of the work I did on it, work that is usually part of the author’s responsibility.

“In substantiation of my claim, here is a partial list of my work on the book.

“1. Research. I have done most of the research for his book. I spent many Saturdays in the NYPL and many full days in the BPL as well as in the Fairhope, Asheville, Newton, and Keene libraries, bringing back stack after stack of informative notes. I spent a summer at Widener in Cambridge, made research trips to three colleges, and did research in historical societies in Detroit and Keene. I also brought home for study numbers of books and dissertations ordered through interlibrary loan, studied them, and took notes from them.

“My work on the research has been a key factor in the book’s development. I have good control of the subject matter and know the sources.

“2. Analysis. I sifted, analyzed, and organized all the research, putting it into a form that would make it intelligible and from which the writing could be done. I produced hundreds of pages of outlines interpreting as well as quoting from the research. This analysis took uncounted hours of study.

“Without this analytical study, the writing would have been impossible. This kind of study of the material is usually done by the author.

“3. Writing. I wrote the final thirteen chapters of the book. You edited them. In other words, at this point we exchanged roles. [Your Oxford Editor Sheldon] Meyer likes the chapters. You called some of my work on these chapters ‘terrific.’

“Moreover, each chapter took me less than a week to write, partly because I am completely at home with the material, having done the research myself.

“If I had not taken hold of the writing when I did, the manuscript would not now be done. [Seymour asked me to do this writing; I did not volunteer to do it.]

“I have therefore written about a third of the book.

“4. Final revision. As I input the final version of the manuscript, I edited as I went along, cutting the unnecessary parts that Meyer wanted removed and improving the manuscript in every possible way.

“My insistance on getting a computer for the manuscript was another key factor in the speed with which the work could be completed.

“5. Editing. I edited every bit of writing every step of the way, revising as necessary. I sometimes rewrote entire sections as well. The editing work on the book amounted to a task I handled daily.

“6. Correspondence. I handled the correspondence related to the research. When a letter needed to be written for information, I wrote it. I handled correspondence for illustrations, too. The wording of these letters took time and thought.

“7. Typing. In a manuscript as long as this one, where the chapters sometimes went through seven drafts, typing became a major burden. I estimate that I typed about 8,000 pages, counting my work on the outlines. This took time, energy, and attention.

“8. Clerical work. I filed, organized, and kept track of everything. This includes all research notes, documents, bibliography, and illustrations. I have taken care of the copying and mailing. If something is needed, I find it.

“9. Illustrations. I am preparing the captions, credit lines, and expense list.

“10. Bibliographical note. This piece will be a major task and could take several weeks of work. I will no doubt be doing most of it, since I am so familiar with the materials used.

“11. Index. As before, you want me to handle the writing of the index, a tedious task that is the responsibility of the author.

“12. Publicity. I am the logical person to handle this work, since publicity is one of my skills. I expect to spend considerable time planning and carrying out publicity.

“Any combination of some of the above responsibilities entitles me to have my name on the title page, as it should have for Volume 2.

“Since the book was your idea, you should be considered the Senior Author, but if you are the Senior Author, than I am surely the Junior Author. The attached [suggested] title page reflects that relationship.

“You’re concerned with the way your name will appear in the book. I, too, am concerned with the way my name will appear, and in view of all the work I put into the book — devotion is not too strong a word — I do not think it fair for my name to appear only in the acknowledgements, among people who might have sent in an article or cooperated as a librarian. Yet I should be mentioned there. Below is a paragraph about my contribution that I would like to appear in the acknowledgements:

“‘My wife, Dorothy Z. Seymour, an editor and author, worked closely with me on the preparation of this book. She did most of the research, carried on the correspondence, and did all the typing and clerical work. She analyzed and organized the mass of material collected through research and put it in a form from which the writing could be done. She also edited the writing as it was produced, and she wrote the first drafts of thirteen of the chapters. Moreover, with my participation she performed the final revision of the manuscript as she input it into the computer.'”

The wording of the title page I wanted was this: Baseball: The People’s Game Harold Seymour, Ph.D. with Dorothy Z. Seymour.

It never happened. Seymour could not bring himself to acknowledge that I had made such a significant contribution as to actually be revealed as co-author of the book. My name is, as usual, mentioned on the Acknowledgements page, but nobody realized my real contribution to the work until after his passing. His publisher had no idea of what I had done — he even hired me to edit the book! — until afterwards. That would not have happened if the publisher had known I was also the book’s co-author.

When Baseball: The People’s Game was published in 1990, it won three prizes. By the following year I suspected that Seymour had Alzheimer’s Disease. Seymour was invited to accept the Casey Award in person, but he didn’t feel up to travel, and I arranged for his brief acceptance speech to be recorded with a video camera and sent to Mike Shannon of Spitball Magazine. When Ken Burns, who lived and worked in nearby Walpole, came over to Keene to film an interview with Seymour for his celebrated documentary, he was very kind, but later he found the results unusable.

Soon Seymour could hardly walk and was becoming too difficult for me to handle. He refused to permit me to bring in outside help. I finally had to place him in a nearby nursing home, where I visited daily. He passed away in September of 1992. His will called for the delivery of all our sports materials, including books, notes, microfilm, dissertations, magazines, outlines — everything, including the unused notes for projected books — to Cornell University Archives, along with trust-fund money to support the necessary work to accession them. I saw to that delivery. The materials of the Seymour Collection are now available to all scholars at the Carl Kroch Library at Cornell in Ithaca, New York.

I’ll always be grateful for the opportunity I had with Seymour to learn research techniques. It was in the school of baseball, so to speak, that I learned to love history and historical research. I put this knowledge to good use in preparing my new historical novel, The Sceptre, which took ten years of research and writing. It even includes a little baseball.

When I began work on this novel in 1987, I worked on it in semi-secret. (Barbara Tuchman used to hide books under the living room sofa when her husband came into the room.) Seymour demanded to know what I was working on, and my admission that I was writing a novel was met with scorn: “You can’t write a novel,” he scoffed. His disdain hurt me, but I was determined to produce the work I had in mind.

Simply determined, because I knew I had the right skills. I worked on it every chance I got, between the efforts to complete Seymour’s book, fulfilling editorial assignments, and writing articles and stories. Into this book I have put much more of myself than anything else I’ve ever done, including details gleaned from my family history.

I realize now that in writing about the development of a character based primarily on my mother, I also wrote of my own gradual development into an independent person.